- Home

- Ken Webster

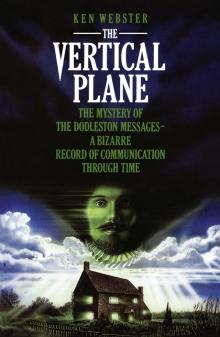

The Vertical Plane

The Vertical Plane Read online

Copyright

Thorsons

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by Grafton Books 1989

This edition published by Thorsons 2017

FIRST EDITION

© Ken Webster 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover illustration © Steve Crisp

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Ken Webster asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Poem XXVI ‘This is the first thing’ from The North Ship by Philip Larkin reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008292645

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008292645

Version 2017-12-04

Dedication

For H

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Postscript

Picture Section

Further Reading

Notes on the Messages

Appendix: the Language of the Messages by Peter Trinder

Footnote

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

This book is a record of a most unusual set of communications. They are described in the everyday context in which they occurred. It is therefore not a scientific document, but it does contain observations at first hand from a number of reliable persons. Despite the necessity of selecting from the communications I feel that this book is faithful to the events it portrays. I hope that the interest – and perhaps controversy – that this book will generate will not centre on the brief notes at the end of the book where I offer some personal thoughts on the genesis of the messages. These notes are simply to encourage discussion, for in all these matters I am acutely conscious of the inadequacy of my own knowledge. But I share the opinion and optimism of Sir William Crookes who, when asked to explain how the psychic, D. D. Home, managed his feats, retorted: ‘I didn’t say it was possible, I said it happened!’

Chester, May 1988

Prologue

Most people do not take heed of the things they encounter nor do they grasp them even when they have learned about them, although they suppose they do.

Heraclitus (Fr 57)

DODLESTON: four miles south-west of Chester in that anachronistic enclave of Cheshire on the Welsh side of the Dee.

Take the Kinnerton road from Chester – leave behind the suburbs of Westminster Park and Lache – turn left through the dark ribbon of Bretton Woods. Dodleston one mile.

Ahead flat Cheshire farmland runs carelessly towards the first Welsh hills, Hope Mountain and beyond that the high moors of Minera.

Along the lane appear the chicken wire and weather-boarding of the hunt kennels; the maize fields and ancient Greenwalls Farm are hidden by decaying orchards. The road is uneven, showing the effects of council neglect and the filth of tractors and animals by turns. A sharp right and left and there, tucked shyly into the verge, is the village sign.

Half the village is a dormer for the heavily mortgaged. The rest live on two roads. Church Road connects, at one end, the village school and a small council estate to the Red Lion, church and village hall at the other. Bisecting Church Road is Kinnerton Road, which contains two more pivots of village life. Firstly Mr Hughes’s shop and post office, Chapel Stores, and, further along, the farm from which milk deliveries are organized early each morning.

The name Chapel Stores bears testimony to some of the dissonant influences acting upon this otherwise quite typical Cheshire village. Welsh nonconformism built the tiny chapel, flourished briefly then withdrew, leaving only the building. Facing it are the hard Ruabon brick houses, built by the Duke of Westminster, which represent the deeply conservative tenor of rural life. Each has a ‘W’ picked out in blue bricks across its upper storey as a permanent reminder of the all-pervading influence of the English aristocracy.

Many of the Duke’s villages and hamlets find their names echoed in expensive areas of London: Belgravia, Eccleston Square, Eaton Square. But not Dodleston. For in truth Dodleston was never entirely beholden to the Grosvenors.

And there it rests between the Welsh border, a mile across the drained and empty lands of the Burton Meadows, and the Duke’s estate at Eaton.

From the Welsh side, from Town Ditch and Golly, Dodleston can be seen clearly, straggling a low ridge above the Meadows. A castle mound and its trees form one landmark and the twin silage towers of Moat Farm another, but clumps of trees and then ones and twos break up the middle distance. This settlement, one thousand years old in 1982, settled for insignificance centuries ago. It is a place both confident and obscure.

Dodleston is not quite spoilt, and consequently the village is brimful of would-be squires, aspiring businessmen affecting concern and love for the slower more sentimental pace of rural life. So the Red Lion car park has its scattering of XJSs and Porsches but very few are in awe of this kind of ostentation. The landlord’s coffers increase ‘at the same rate as the girth of his sons’, said someone unkindly, but equally Frank Cummins, a die-hard villager in a demob hat and coat, will be found fixing planks with secondhand nails. The village has no dominant group and although the ebb and flow of traffic along its roads points to many changes it is an even-tempered place. Sometimes the tempo changes at weekends, when the roar of motorcycles and modified Ford Escorts marks closing time or the sounds of a party drift across the houses. For the rest, the years bring noisy adolescents to the phone box at the junction to kick footballs, tin cans and occasionally each other, until they tire, grow older and gain entry to t

he pubs, falling in and out of love and the minicabs which ply to and from the city clubs.

Meadow Cottage stands between Chapel Stores and the phone box, the third in a row of four, tiny, 18th-century dwellings facing onto Kinnerton Road.

It is accessible at the front from Kinnerton Road and at the rear by Church Road. The village passes the door. Children throw wrappers and Coke cans into the small front gardens across the knee-high brick wall. In the sharp, raw mornings cars queuing alongside its gate, their engines ticking over excitedly, clog up the road by the shop. This is my house. It is late autumn 1984.

1

Nicola Bagguley stood with her luggage on the pavement outside the funeral director’s in Delamere Street, Chester. I pulled across to her side of the road and parked on the double yellow lines. It was six o’clock in the evening and dark. The city was shutting down for the day and the traffic circulated slowly and painfully, all steamy exhausts and stoplights up and down the Ring Road. Despite this I was happy. Seeing Nic was always essentially soothing. She came perhaps in the hope that I knew something of the whereabouts of Rob Jones, a good friend, but the transatlantic wires were quiet and had been so for three months. Perhaps she also came for the company and to see how the renovation of the cottage was progressing. I had made much of the rigours of living without kitchen or bathroom all summer; of the money I’d spent and the frustrations of it all. Deep down I was pleased just to be able to sit on my own settee in front of my own fire without moving a bag of cement. Nic’s being here was a statement of intent, signifying normality, simple pleasure and a better end to a shaky year.

Nic was broke, having come back from three months in East Africa. She had been living less than salubriously in hotels and trains which had insect infestation and bugs by the squadron. The better hotels, she said, had canisters of a spray called ‘Doom’ which, far from killing the roaches, served only to stimulate them. As Nic related her experiences it became clear that she had not escaped from her own recent past: teaching, unsatisfactory relationships, a sense of time slipping away. Life at the cottage, if not ideal, was a marginally better proposition for her. In return she was to help redecorate.

I was emerging from a long, terrible six months which had seen all the downstairs of the house gutted and then restored. There had been months of living in one room with only a kettle and dust for comfort. That and teaching. I was shattered. But for a holiday in Austria with the school last half term I’d have crumbled. Debbie, my girlfriend, stayed with me through the building work but our relationship suffered; it felt as if cement dust was eroding it. Now the work was all finished on the ground floor but it made the upstairs look shabby. Another season of work was inevitable but, please God, not until spring.

Some people love to tinker with their homes, but not me. I do what I have to do. This now meant decorating the finished part. Painting was on the agenda and alternating with bouts of eating wholemeal pizza, drinking wine and a few quarts of tea, some painting did get done.

‘What’s this?’ asked Nic, pointing to some marks on the wall between the bathroom and kitchen. ‘Has someone been putting their feet on here?’

I went over to her. ‘They do look a bit “footprinty”, don’t they? You’ve got to be in the right place to see them. They’ve been there for ages.’

‘Whose feet are they?’

‘No one has owned up, too small for me or Deb. Deb says she can see six toes in the print.’

We laughed. All three of us began re-examining the dusty outlines for signs of an extra toe. Opinion was mixed. We then imagined how it was done, whether it was by standing on a chair or the table or both, for after seemingly emerging from the small, oblong electric wall heater they ambled diagonally upwards as far as the edge of the ceiling.

They had appeared in late August or September 1984. No one had much to say about them other than that they were size five. Quite obviously somebody was fooling around. By late autumn they were very faint indeed.

I remember those footprints disappearing and the kitchen area growing more homely as colour replaced concrete drab and grubby first coats.

At night Debbie and I slept in the front bedroom on an old creaking bed with a lumpy feather mattress. Nic got the back bedroom with the four-track recording equipment, electric guitars and a single mattress on the floor.

The morning after the footprints were painted over I had been downstairs to the bathroom and passed through the kitchen perhaps twice before I looked closely at the wall (life’s too interesting to spend time wondering about walls) but it stopped me in mid-stride when I did look. The footprints had returned. They were not exactly in their former position so it was not possible that they were the old ones come through. They were new, six-toed, composed once more of dust from the floor. I called the girls. Nic and Deb came down, they were more than just puzzled and Nic was, I’m certain, quite horrified. She had painted them out the day before. I thought she was just about ready to pack her belongings and go.

None of us had stirred that night, but we asked ourselves all the usual questions about whether the door had been closed and so on. We decided that one of us must have developed a strange form of sleepwalking. Nic soon recovered and was persuaded to stay, but equally none of us felt easy about it. The footprints were painted out once more. They did not reappear but, like children, all three of us avoided going downstairs in the night.

2

Some two days after the footprints had been painted out for good and the entire episode was beginning to seem hilarious we made a large-scale foray to Chester to stock up on food. On our return we left a raggy pile of about a dozen catfood tins on the floor and too many packets, tins, loaves and so forth tucked into too little cupboard space. Nothing was done about sorting all this before bedtime but by morning the catfood tins were neatly ordered in imitation of a human pyramid, striking out from the brick corner pillar towards the fridge like a peninsula on a rocky coast. On top of the pyramid were three further tins. I discovered this piece of silent housework at about 8.00 A.M. and stood there gazing at it, all the while trying to remember if I had heard anyone get up in the night. The girls regarded it with a mixture of interest and trepidation. There followed a breakfast time edition of ‘Any Questions’.

The principal suspect was John, a lazy guitar player who, along with keyboard player Stennet, often used the little four-track in the back bedroom. They had pretty free access to the place. John in particular was keen on seeing Deb and had been whiling away a largely tuneless couple of hours here every few days. Nic was convinced he was a likely culprit as he had a very strange sense of humour. I was not so sure. The cottage was not particularly secure; almost anyone could get in with a little effort. Why bother with footprints and making mock-art structures out of catfood tins?

Next morning there was no disturbance but the following night another stacking occurred. This time we found a single column approximately four feet high composed of a couple of two-litre bottles of lemonade, a packet of dry catfood and a kitchen roll. It was a precarious construction. It looked a little too good for John.

Slowly a sense of unease permeated the cottage and its inhabitants. The outside doors were more rigorously checked at night, the windows shut. It was affecting our imagination, and the creaking of the ceiling or furniture, previously unnoticed, became a matter for concern. One night Nic thought she saw a dense shadow pass her window above the kitchen. Deb and I awoke simultaneously the same night because we thought someone was in the room. In both cases there was nothing there. Sleep became less settled. Anxiety came with darkness; a sense of foolishness with daylight.

Meadow Cottage is very small for three people. If I wanted to be alone I would drive a dreadfully noisy but reliable Volkswagen out on to the lanes and just motor for an hour or two. After one such occasion, a few days after the stacking of the lemonade bottles, I returned to the cottage to be told that there had been a further twist. It was a calm, mild December evening. Nic and Deb had been sit

ting around the fire chatting when the temperature had dropped slightly and a strong gust of wind drove under the door from the kitchen. It was forceful enough to catch the day’s paper, which was folded up on the floor about six feet from the door, and take it capriciously up into the air above the level of the chair arm. It came down in three sections. Other pieces of paper were also scattered. Nic and Deb looked at each other in silence for a few seconds before Nic suggested checking the back door and the kitchen window. All was secure. John wasn’t responsible this time. A freak of nature perhaps, but our sensitivity to the slightly unusual was not about to be alleviated.

Nic had left her job teaching English in July. She vaguely planned to join or create an ‘alternative’ cabaret band in the hope of gaining enough performing credits for an Equity card. To this end she wanted to write sketches and dialogue in preparation and I suggested that she use a word processor as it would be smarter and more creative than a typewriter. She could cut chunks out, stick them in different places and get a perfect copy every time. Hawarden High School, where I taught, had over a dozen simple but useful BBC microcomputers and at least eight containing the word processing chip EDWORD. Perhaps one of the reasons I went to the trouble of booking, collecting and delivering a computer, disc drive and screen to the cottage was quite selfish: Nic was full of energy and enthusiasm and at that fag end of the autumn term it was hard to find enough emotional energy to match hers. Give her a computer and she’ll entertain herself, I thought. And so she did.

Providing you remember to get a ‘floppy disk’ to store your work on, a word processor is very simple to use. I explained to Nic that all she needed to do was type in *D, press RETURN and then * EDWORD, another RETURN and the word processing system was there, all ready to go, with a simple menu of choices before you on the screen. You can create a document, revise one you have begun, just look at it, or look at the index. I told her that every piece of work, every file, has to have a name. These names are kept by the computer on an index so it is easy to find your work or check what other work is held on the disk you are using. It was designed for primary-school children and is simple and fun. We set it up in the kitchen as the only table we had was in that room. She loved it to bits and slogged away for hours.

The Vertical Plane

The Vertical Plane